Jodi’s Journal: Want to know why your business can’t find workers? Meet the one I found

Sept. 26, 2021

I couldn’t tell you how many interviews I did last week, but I can definitely point to the most memorable: Janai Stoopes.

We spoke for only about 10 minutes, but I bet I’ve told her story 10 times since then.

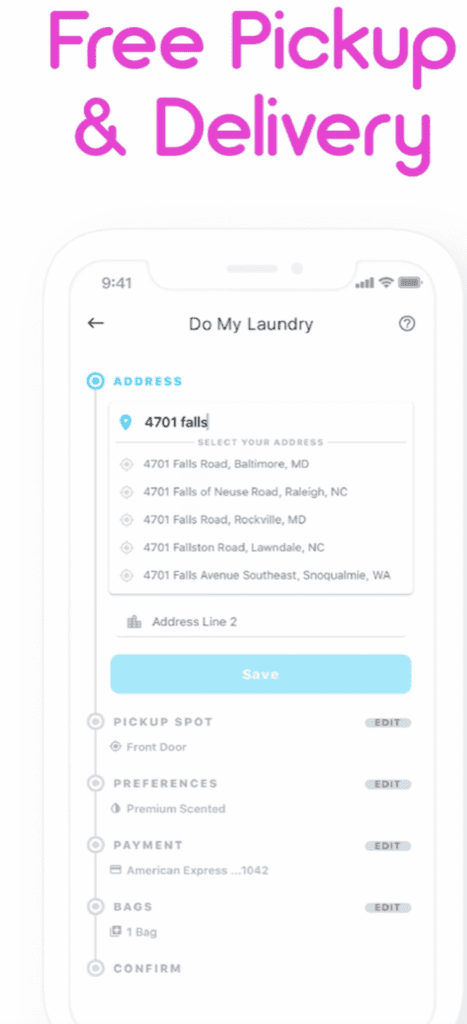

Stoopes is one of the first “Sudsters” in Sioux Falls. She works for SudShare, which its founder described to me as the Uber of laundry.

Using an app to connect with customers, Sudsters pick up customers’ laundry outside their home, wash, dry and fold it, and leave it back at the home the following day.

For Stoopes, a single mother of two, “it works out perfectly,” she said.

“I’ve always wanted to be the type of mom where I was able to drop my kids off at school and pick them up and go to their activities, and I’m a single mom, so I don’t have anyone to help me with those things. It’s on me, and gig work works out perfectly.”

She found SudShare while looking up other gig economy roles to supplement her work with Instacart and Shipt, where she delivers customers’ groceries, and a newer one, Handy, where she does house cleaning in partnership with Angie’s and HomeAdvisor.

“How much do you work?” I asked her.

It’s equivalent to a full-time job, “about 40 hours a week, sometimes more,” she said.

“What about before that?” I asked her. “What did you do?”

Wait for it.

“Before this, I was doing factory work,” she said. “I did both for a while. And now I’m just doing (gig work) full time.”

If you are in manufacturing, or logistics, or food processing, think about that. Stoopes could have been one of your employees.

And, unlike what some continue to insist to me, it’s not that she’s sitting at home relying on government assistance. It’s not that she just decided to drop out of the workforce.

It’s that instead of working on a production line, she’s in her car delivering other people’s groceries or in her laundry room washing and drying their clothes.

And she loves it.

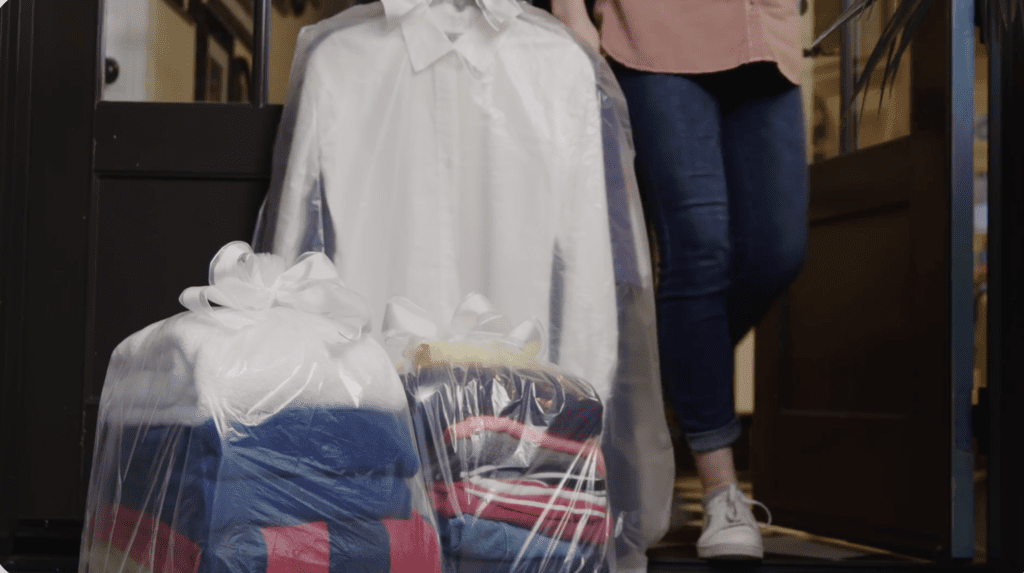

“I wash them at home and dry them, and right after they dry, I fold them so they don’t wrinkle,” she said. “I make sure I fold each individual family member in different piles, and we have clear bags that we put the clothes into, and I usually tie mine up with a bow and leave a nice little note.”

At any other moment in time, someone like Stoopes would not be able to essentially act as an entrepreneur, controlling how much and when she works.

I realize it’s not a revelation that the so-called gig economy has been offering alternative work options for a while now. But there was something about putting a face to it and about connecting how this person used to work in manufacturing that brought our current workforce challenges home for me.

I had found out about SudShare because its CEO and co-founder, Mort Fertel, had pitched the Baltimore company’s expansion to me in an email. I get a lot of these – every day – and most of them get deleted in a matter of seconds. But something made me reply to him.

I’ll do the story, I told him, if you find me someone in Sioux Falls who is doing this.

And after I’d talked to Stoopes, I had to talk to the CEO as well. Who knows – this might be my chance to interview the next great industry disrupter.

Actually, I probably should have interviewed his son, Nachshon, who really started the business at age 17 after his mother tasked him with doing laundry.

“He’s like, no way, but I’ll build you an app,” Fertel said. “We thought he was kidding, but he wasn’t.”

Fast-forward a few years and the father and his two sons “are basically running the business.”

It’s unique in the gig economy in that it’s manual labor that can be done from home, he pointed out to me.

“It’s great for stay-at-home moms and dads and other people who want to work from home,” he said.

“So how many Sudsters are there?” I asked him.

“About 45,000.”

I about choked.

“You have 45,000 people doing other people’s laundry?” I replied

Yes. Yes he does.

“Technology has transformed our lives, but the chore that takes the most amount of time in a household has not been affected at all,” he said. “It’s really ridiculous, and I think that’s why it’s really taking off. Because it’s so needed.”

Clients pay $1 per pound of laundry, with 75 percent going to the Sudster.

The company tells Sudsters they can earn $15 to $20 an hour, and Stoopes told me that’s accurate.

“We’re really a technology company, but we’re not even that,” Fertel continued. “What we’re really selling is the most precious thing on earth: time.”

In this pandemic time, “people have become very sensitive to their mortality and realizing that’s what we have on Earth here is just time,” he added. “What do I want to do with it and how do I want to spend it? Very few people answer that question with doing laundry.”

If you’re Stoopes, you answer it by saying you want to drop off your kids, pick them up at school and go to their activities.

That’s why she quit the manufacturing job for the gig economy.

I see it in my own business constantly. My ability to attract and retain talent is highly influenced by my willingness to offer them as much control over their time as possible. That’s not always easy in a deadline-driven job. I fully recognize that working for us comes second to whatever is going on in their lives and that they will prioritize their time accordingly, and as a leader it’s ultimately on me to make it all work.

That’s clearly more doable in some industries than others, which explains why some are suffering so acutely for workers, I think. You generally can’t let front-line health or safety workers create their own hours or work environment. Someone has to be in the kitchen cooking when the customer is there to eat. You can’t assemble a complex product or process a hog from home.

But we as leaders also can benefit by thinking more like that teenager in Baltimore. And by remembering that just because we don’t necessarily see them, workers like Stoopes are creating their own version of work.

Here’s something else to keep in mind: Many workers in the gig economy might like the freedom and earning potential, but they often don’t have much good to say about their companies. The Fertels say they’re out to change that.

“We consider our Sudsters like our family,” he said. “Our relationship with them is unbelievable. We love them, and they love us, and we’re in constant communication.”

It’s possible to build culture and loyalty even in a more fragmented workplace. But, again, it takes a more modern approach.

Fittingly, right after I spoke with my first Sudster, I stopped by Talent Draft Day, an event hosted this year by the University of Sioux Falls and organized by the Sioux Falls Development Foundation that brought together high school and college students to talk about career pathways.

USF president Brett Bradfield was one of many who heard me retell the story of the Sudster I’d just met earlier that day.

It didn’t surprise him, either.

“I’ve had some people ask me when I think things are going to get back to normal,” he told me.

Neither one of us said anything for a moment, probably thinking the same thing.

Forget normal. Change and disruption are the new normal. And if you’re struggling to hire, don’t forget about people like the Sudster.