Pioneering COVID-19 treatment leads Sioux Falls biotech company to big opportunities for growth

Sept. 23, 2020

In an isolated space at Sanford USD Medical Center, a patient diagnosed with COVID-19 was hooked up to an IV.

For about an hour, that patient was infused with antibodies unique to anything else in the world.

It’s a highly concentrated dose of human antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

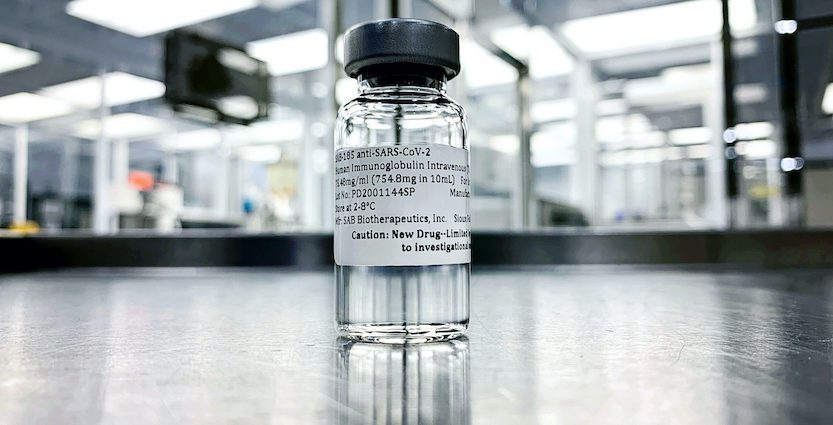

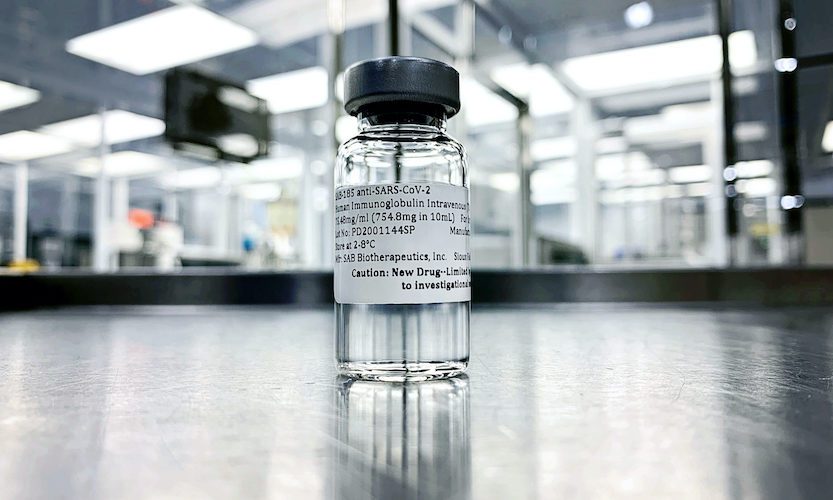

The treatment, called SAB-185, was developed and produced in Sioux Falls by SAB Biotherapeutics. And it is being tested for the first time in a COVID-19 patient in Sioux Falls at Sanford Health in a clinical trial that began within the past month.

“It’s the first of its kind of this type of therapy,” said Dr. Susan Hoover, an infectious disease specialist at Sanford and chief investigator for the clinical trial.

“This is obviously very innovative.”

Start with the fact that the antibody-filled plasma is produced in cattle genetically engineered to produce human antibodies. The only other way to secure plasma with these antibodies is in patients who have recovered from COVID-19.

“But in cows, they’re able to produce and purify much larger quantities of product than we could from a human being donating convalescent plasma,” Hoover said.

Not only does the cow donate a lot more plasma than a human, but the high concentration of antibodies means a one-hour, one-time infusion is expected to be enough to activate the patient’s immune system and neutralize the virus.

“I’ve been following them (SAB) for several years, and this is their first opportunity to treat patients in the U.S. with an infection that is unfortunately quite common here in the U.S.,” Hoover said.

“I think it’s a very good opportunity for them to start fulfilling some of their potential.”

For SAB, COVID-19 represents an opportunity to show how biotechnology decades in the making can address not only infectious diseases like the coronavirus but also influenza, autoimmune disorders and even cancer.

The same approach that can supercharge a patient’s immune system to fight COVID-19 can address other diseases, the thinking goes.

And big players are buying into it. This year has brought $72 million in government funding to advance SAB’s capabilities, specifically around its COVID-19 therapeutic. It’s one of only nine companies with a therapeutic being funded as a medical countermeasure to COVID-19 by the government’s Biomedical Advance Research and Development Authority and the only one using its novel approach.

Earlier this year, SAB began working with global biotherapeutics leader CSL Behring to more rapidly scale up and deliver its therapeutic. This summer, a new $14 million Series B investment in SAB included global health care leader Merck.

“SAB is a very different company today than we were at the beginning of the year,” founder and CEO Eddie Sullivan said.

“And I guarantee you toward the end of the year we will once again by a very different company in three or four months than we are today. That’s how quickly things are moving.”

Combatting COVID-19

SAB was positioned to address an outbreak such as COVID-19 before there was such a thing as COVID-19.

In the past year, the company had started a process with the Department of Defense to prove it was capable of rapidly responding to emerging infectious disease threats and pandemics.

That was “without knowing that in a few short months we would be in a real-world situation,” Sullivan said. “For SAB, this has given us the opportunity through work we’re doing (with the federal government) and collaborations around the country and really around the globe to produce a specifically targeted, human polyclonal antibody to this virus.”

While other bioscience companies have made headlines trying treatments against COVID-19 using monoclonal antibodies, SAB is the only one to attack it with specifically developed, human polyclonal antibodies – the way the human body was designed to fight these kinds of viruses – without the need for human donors or serum, Sullivan said.

“The natural way is a polyclonal response, where you have literally thousands of antibody species binding to multiple places on the target, and that allows the immune system to work with those antibodies and literally activate the rest of the immune system within the patient,” he said.

“The other component is that viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, mutate. Polyclonal antibodies are binding to multiple targets on the virus, and it’s nearly impossible to mutate enough to completely escape the efficacious value of a polyclonal antibody.”

SAB began testing its therapeutic against COVID-19 in 28 healthy participants at the State University of New York in Syracuse and soon after began testing in 21 COVID-19 patients at Sanford.

“Our trials are double-blinded, randomized, controlled studies,” Sullivan said. “We are being very conscientious about conducting trials that will give us the results we need in order to have a licensed product as quickly as possible.”

Because the trials are blind, even physicians at Sanford won’t know yet how patients could be responding. Once the hurdle of proving the treatment is safe has been cleared, a phase two trial will test its effectiveness.

Those are expected to start in early fall, Sullivan said.

“Phase two and three sites haven’t been selected yet,” he said, adding he expects they will be done at multiple sites, and “Sanford would have obviously the same capacities they’ve had with other clinical trials they have conducted to participate should they choose to.”

The initial patients enrolled in the trial are in the early stages of COVID-19 – testing positive a week or less before receiving the treatment – and they have not progressed to the point of needing hospitalization.

“Unfortunately, we’re seeing a lot of COVID-19 in our community right now, so we have good potential to reach out to patients who have been diagnosed,” Hoover said. “And we’re at a time where we don’t have many options for people with COVID-19 in terms of treatment – people who are fortunate enough not to need hospitalization, they might be moderately sick, so there’s large interest in offering those patients something they could potentially participate in.”

Sanford continues to recruit patients for the current and potentially future phase of the SAB trial.

“I’m also very happy with how Sanford has stepped up to this,” Hoover said. “This requires coordination from a lot of people at Sanford. We need to bring people with COVID to the hospital for these visits, and many staff in many departments are coordinating to make that happen safely and efficiently.”

By the end of the year, SAB hopes to be close to completing phase two of the clinical trial and advancing “into the broader final trial that will allow us to move to licensure of this product,” Sullivan said.

The goal is that SAB-185 would prevent people from reaching the stage of severe disease. Patients with comorbidities or a high likelihood of severe complications would receive the treatment “as early as possible,” Sullivan said.

“And prevent them from getting into severe disease. Because once they get into severe disease, we will still be treating them but that’s not where we will do the most good.”

The federal investment in SAB was touted last week in a New England Journal of Medicine piece authored by representatives of the government’s Operation Warp Speed, who highlighted the development of the company’s antibody product.

Operation Warp Speed “is investing at risk to scale up production from this herd of cows so that tens of thousands of doses could be manufactured this year,” the piece said.

Even after a vaccine is developed, there will still be a need for therapeutics, Sullivan added.

“Our technology is not in competition with vaccines,” he said. “There has been an influenza vaccine for years, and yet there’s still a significant need for a powerful therapeutic for influenza. We lose tens of thousands of people every year to influenza; because while there is a vaccine, not everyone responds the same way, and we have significant losses. They are both needed in any kind of response to these infectious diseases.”

Influenza trial, future potential

Influenza is at the forefront of Sullivan’s mind too.

SAB concurrently has started a phase one clinical trial of its treatment for influenza.

“The idea is we will complete that phase one trial early next year and move immediately into advanced clinical trial,” Sullivan said. “We expect to conduct those around the globe, not just in the U.S., and we’re looking at a strategy to move our influenza products where we will produce a product for the Southern Hemisphere part of the year and the other part of the year we’re producing it for the Northern Hemisphere. That’s ultimately the vision.”

The goal is to move as fast as possible to prove the treatment is safe and effective, but it will be a “more traditional time line” for product development compared with COVID-19, “which is on a very fast track,” he said.

“I don’t expect everyone who gets influenza will receive an immunotherapy like our product, but certainly people at risk and who have comorbidities or are elderly and have a diminished immune response will benefit from having these products available.”

While SAB’s treatments are delivered intravenously at this point, the company is looking at how to potentially deliver it using an injection.

On the ground in Sioux Falls, the company’s growth has been multifaceted this year.

Plasma production has scaled up consistently, as has purification.

“The capacity building we’re doing and the work we’re doing on COVID is not related just to COVID but SAB’s overall rapid-response capabilities for emerging diseases and pandemics,” Sullivan said.

“What SAB is building is South Dakota is that rapid-response capabilities for future threats, and in addition we’re building capacity within the company for things like influenza, type one diabetes, we’re working on very exciting oncology prospects using our technology, so the stakeholders that are involved with SAB need to know this is allowing us to expand our capability to develop not just products for emerging diseases but multiple products we believe are going to be very exciting for the future of this company.”

Many of SAB’s early investors were South Dakota-based, including the Sioux Falls Development Foundation, South Dakota Equity Partners and numerous individuals.

From an economic development standpoint, those investments already are starting to pay dividends. SAB’s staff has grown so fast this year that Sullivan needed to check with human resources for the most current number, which as of this writing was approaching 80.

“Two years ago, we had 20,” he said.

“So SAB is growing very rapidly, and we’re very excited to be doing this in South Dakota in all aspects of what we’re doing as far as our capacity building and business development. We are recruiting phenomenal individuals into our company, and many of them are local. Our chief medical officer is from Maryland, and others have come from out of state, but we are getting very talented individuals from the local and regional area … and SAB has a much broader outreach through our collaborations outside the region, so we are very excited.”

SAB Biotherapeutics will be featured on a panel discussion about post-pandemic opportunities and challenges in the biotech industry at the 2020 South Dakota Biotech Summit on Sept. 28 and 29. The program will be held virtually. To learn more and register, click here.