Krabbenhoft on Sanford merger: ‘This is good for business’

Nov. 2, 2020

For at least a decade, Sanford Health CEO Kelby Krabbenhoft has carried a small piece of paper attached to the inside of a leather portfolio he uses daily.

There’s a name at the top.

Then a question.

And then seven short bullet points.

The name is Mike Leavitt, former governor of Utah, who served under President George W. Bush as secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Any project of scale requires an architect and a builder. And in the case of the newly announced merger planned between Sanford and Utah-based Intermountain Healthcare, Leavitt could be considered the architect.

Farther down on that piece of paper that has guided builder Krabbenhoft’s growth strategy for years are those seven bullet points he dubs Leavitt’s rules. They’re qualifying characteristics needed for health care organizations to succeed in the future.

There’s more simplicity than mystery to them: Things like amassing enough capital to take risk and provide infrastructure. Managing risk. Brand recognition and trust. Simple to articulate, yet so hard to execute that no health system yet likely would claim to have achieved all of them.

“It takes a lot to live up to those rules,” said Krabbenhoft, who calls Leavitt a friend.

“He hasn’t really given me insights on what to do, but he’s framed it in a way that’s nationally consumable.”

Leavitt, whom Krabbenhoft recently asked to join Sanford Health’s board of trustees, was the one who introduced him to his future successor, Intermountain CEO Dr. Marc Harrison. The two first met in April. Harrison, a globally recognized thought leader, led international business development for the Cleveland Clinic before coming to Intermountain in 2016.

Leavitt also likely will chair the board of the combined organization following the term of Intermountain board chair Gail Miller.

The former HHS secretary anticipated mergers such as the one Sanford is embarking upon years ago. In a 2011 column for Modern Healthcare, he spelled out the same elements that made their way into Krabbenhoft’s notebook and said:

“Since no one entity singularly possesses all of these features, health care players are joining forces and combining the necessary assets to be accountable for clinical and financial outcomes.”

And, in that same piece:

“The Greek philosopher Heraclitus made famous the idea that nothing endures but change,” Leavitt wrote.

“While change is admittedly difficult, health care consolidation holds great promise. It will unleash a health care system that provides more attention to patients and more accountability to budgets. The combination of human compassion and economic dispassion will become the winning formula in health care.”

Change could come in powerful ways in the next year to Sanford, the city’s largest employer, because of this merger.

It will move the organization’s headquarters to Salt Lake City, where Harrison is based. It will make Sanford part of an organization of nearly 90,000 employees and bring its combined health plan to more than 1 million members.

“Thank God we aren’t immortal. This run was going to end,” said Krabbenhoft, who became CEO of then-Sioux Valley Hospital in 1996 at age 38.

“There is no mystery here, no hidden secrets. There’s nothing we’re trying to cover up. It’s built for the romance that it looks like. It’s a really exciting thing.”

When 2020 figures are finalized, they’re expected to show the annual revenue of a combined Sanford-Intermountain organization in the neighborhood of $17 billion.

Both are experiencing growth in net income, with Intermountain at a 6 percent to 8 percent margin, and Sanford projecting it will end 2020 at 3 percent or 4 percent.

“I think that speaks to where it is today,” Krabbenhoft said, while adding the scale brought by the merger likely will improve that.

“You can take 1 percent of expenses out without ever touching a human being. It’s in the back room. Purchasing. Utilities. Everything gets touched by a combination like this, and I like doing anything where I don’t have to confront the issue of labor. I love my people. I like giving them raises. I like giving them bonuses. I like hiring lots of people. I don’t want to see cutbacks in staff.”

Despite having to cut back on elective surgeries and make other adjustments for weeks during the spring as the uncertainty of the pandemic loomed, Sanford has gotten to 105 percent of traditional volumes “and just stayed there,” he continued.

“People got scared, and people stayed home, and taking care of minor illnesses got put off, and we talked about how there would be a surge of latent stuff that should have been taken care of, and it looks like that’s going to be a pattern for the foreseeable future.”

While the systems are relatively comparable in size – Sanford, with its Evangelical Lutheran Good Samaritan Society team, has about 8,000 more employees and more hospitals – Intermountain’s health plan is considerably larger, with 900,000 members compared with Sanford’s 200,000.

“This merger is good for business, and I’m not just talking about Sanford,” Krabbenhoft continued. “This is good for business. This is going to drive competitiveness and efficiency in health care premiums. We want to be the best in the country in terms of quality of the care, but beyond that, I want to translate that into that monthly premium.”

Intermountain also is known for exceptional quality outcomes, he added.

“I’ve made no secret of the fact I think Sanford is the unbelievable first-place quality provider in this region,” he said. “Intermountain puts jet fuel in that. I don’t think there will be any question anymore about the differentiation of quality.”

Local impact

Sioux Falls will continue to be a corporate office for Intermountain, where the leader of the east region will be based as a regional president reporting to Harrison.

There’s also expected to be a small C-suite of four or five people reporting to the CEO at the corporate level, with the rest of leadership at a regional level. Krabbenhoft expects members of his leadership team to contend for those roles, he said, mentioning executive vice president Micah Aberson and chief administrative officer Bill Gassen by name but not role.

Krabbenhoft, who increasingly has flattened his own leadership organizational chart, calls the management structure “a critically important issue because what those people decide is how the company performs and its reputation, so it’s really important it’s done right,” he said. “I’m going weigh in on that heavy on my last tour, but Marc and I agreed from the get go.”

He also foresees Sioux Falls could become the “national home” for several core functions of the combined organization, including subacute and long-term care through the Good Samaritan Society, orthopedics, sports medicine and research.

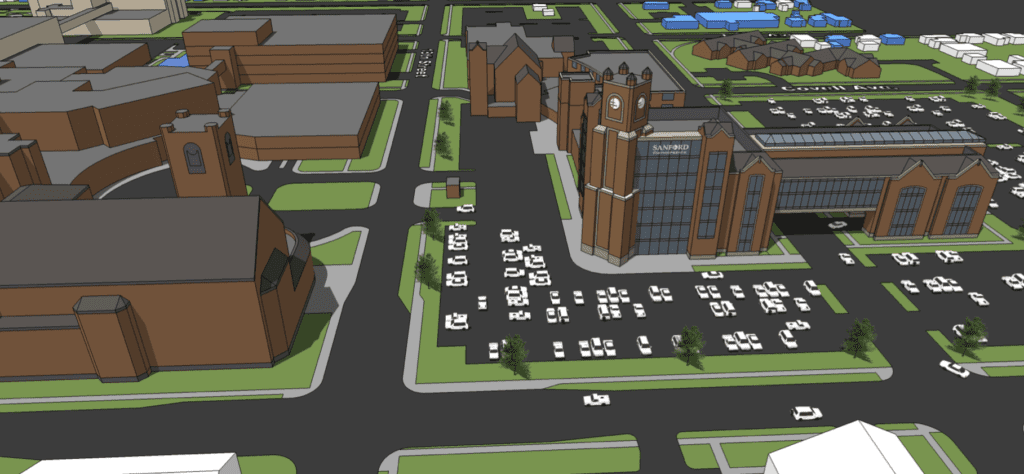

While oversight of the Sioux Falls market is under Sanford Sioux Falls president Paul Hanson, Krabbenhoft continues to hold a vision for the Sanford USD Medical Center in central Sioux Falls, birthed two decades ago, to create “a real boulevard environment.”

Sanford recently took out a building permit for the first part of a planned two-story expansion to the Van Demark Building on the main campus, expected to open in 2022 and add 33,000 square feet for orthopedics.

Other capital investments are expected to continue, including a future medical campus in the southeast part of Sioux Falls at 57th Street and Veterans Parkway.

Krabbenhoft points to it, along with property in southwest Sioux Falls where Sanford once envisioned a research park, as holding “big potential.”

The Sanford Sports Complex, another of his visions, impressed Intermountain, he said.

“Our new merger partners are enamored with it,” he said. “I would probably predict that they would say put one in Salt Lake.”

The sports complex, and other perhaps nontraditional investments for a health care organization, all point back to multiple, consistent guiding principles, he said.

“If it has to do with either education, economic development and/or the health of the community, we’re going to look outside our normal day-to-day routine activity. It’s a way for us to demonstrate in a big way that we’re involved. Otherwise people would say, ‘What are you doing with all that money?’”

But those were his priorities, he acknowledged.

“My board supported my priorities, and I will always be grateful to them for that,” he said. “And I’m kind of glad Marc really looks at the world through the same kind of healthy living, athletically inspired point of view. So I hope that continues. People bet on me while I was CEO here and still am for a little while, and I think we just need to bet on Marc. I like his ethics. I like his priorities. I like his overall view of health and what it takes to be there.”

Merger mode

This time last year, Sanford was in the final stages of a planned merger with Iowa-based UnityPoint Health, which failed on the final vote of the UnityPoint board of directors.

Krabbenhoft has been in “merger mode” before and ever since, focused on achieving the scale that “Leavitt’s rules” dictate is necessary to succeed in the future of health care.

Looking back, had UnityPoint happened, “it might have made the Intermountain relationship not a good deal,” he said. “The fact we are so similar to Intermountain just made for two parties that see the world the same to look at each other and kind of see the same thing.”

Still, he doesn’t rule out the UnityPoint relationship could be rekindled.

“I wouldn’t be surprised,” he said. “Really, all the important elements of what brings two organizations together really were positive, really good. We got distracted by … some things that in the long scheme of things really don’t matter.”

Growing the newly formed, larger Intermountain will be one of Krabbenhoft’s key roles as president emeritus, a position he said he plans to hold until his planned retirement at age 65 in about two years.

“With the momentum these things generate, don’t be surprised if there’s another one right on the heels of this when it gets consummated,” he said. “We have to put our shoulders into getting this delivered. We have to get this in the end zone. The game isn’t over.”

With talk like that, Krabbenhoft shows how the former captain of the college basketball team at Concordia College hasn’t really changed much.

He half-jokingly says of the merger that “all of this is designed around an idea of how to get Augustana (University) to Division I in the Western Athletic Conference.”

He relishes the chance for a reminder that his goal for Sanford Research president David Pearce is still to cure type one diabetes, the endeavor that launched the system into research years ago.

He’s quick to give a rundown of which college basketball teams will be next to tip off at the Pentagon.

While retirement sends many Sioux Falls executives south or west, splitting time in warmer climates, Sioux Falls will continue to be Krabbenhoft’s home address, he said.

“One hundred percent. This is home,” he said. “The culture and the nature of this community, it’s just a great place to live.”

But back to that paper in his portfolio, the one that has come into every board meeting for the past decade.

Along with the name Mike Leavitt and the list of seven organizational qualities, there’s a question.

“Who will win leading the future of health care?”

When a big objective like that is the guiding principle, big bets and big thinking are the only way to get there. All the other moves begin to make sense. And he hopes his successors keep making them.

“I think people want Sanford to keep putting on a good show,” he said. “I don’t hide. And I hope the next crew doesn’t hide. I hope they don’t get scared of criticism. You’re going to get it either way.”

View a one-on-one interview below with Intermountain Healthcare CEO and Krabbenhoft’s successor, Marc Harrison.